My Infrastructure as Code Rosetta Stone - Deploying the same web application on AWS ECS Fargate with CDK, Terraform and Pulumi

Last updated January 7, 2023

tl;dr

I wrote three infrastructure as code libraries for deploying containerized 3-tier web apps on AWS ECS Fargate using CDK, Terraform and Pulumi. This article will provide an overview of my experience working with these three IaC tools and will show how I use my libraries in automated infrastructure deployment pipelines with GitHub Actions.

- CDK Construct Library: github.com/briancaffey/cdk-django

- Terraform Modules: github.com/briancaffey/terraform-aws-django

- Pulumi Component Library: github.com/briancaffey/pulumi-aws-django

- Mono repo with a sample Django micro blogging app (μblog) and frontend app (Vue SPA written with Quasar), GitHub Action workflows for infrastructure and (separate) application deployment pipelines, IaC code that consumes each of the libraries listed above, VuePress documentation site and miscellaneous items (k6 load testing scripts, Cypress tests, docker-compose, etc.): github.com/briancaffey/django-step-by-step

eli5

Pretend we are at the beach building sandcastles. We can build sandcastles using our hands, but this takes a lot of time, and we might bump into each other and accidentally knock over part of our sandcastle. I made some tools for building sandcastles. We have one tool for building a sand castle base that includes the wall around the outside, the moat, the door, and different sections inside the walls. And I made another tool for deploying smaller sand \castle houses inside the walls of the sandcastle base. We fill the tool with sand and water and then turn it over inside of our base and we can build an entire city of sandcastles. Also, the tool lets us carefully remove parts of our sandcastle without knocking over any of the other parts. We can share the tool with all of our friends and they can make cool sandcastles too, and the tool is free for them to use.

Instead of sandcastles, I'm working with computer systems that can power internet applications, like YouTube for example. I'm building tools that can allow me or anyone else to build really awesome internet applications using computers.

The tools are not physical tools like the ones for building sandcastles, but instead, these tools are made with code. The code for websites like YouTube allows you to upload videos to YouTube, but the code I'm writing allows you to upload any type of website (even site YouTube) to the internet. When we run this code, it creates applications on the internet. Also, sand is very expensive and Jeff Bezos owns the beach.

Why I made an Infrastructure as Code Rosetta Stone with CDK, Terraform and Pulumi

To push me to learn more about AWS, IaC, CI/CD, automation, and Platform Engineering

- Learn the differences between major IaC tools and how to use them to do exactly the same thing (build a web app) on the same Cloud (AWS) in the same way (serverless container technology using ECS Fargate).

- Get more experience publishing software packages (npm) and finding the right level of abstraction for IaC libraries that is both dynamic and straightforward

To fail as many times as possible

- Every time I fail when I think I have things right, I learn something new

- Failed IaC pipelines can sometimes be scary, and every failure I have on these projects can teach me about potential failure modes for live projects running in production

- You can oftentimes be "stuck" where you have a set of resources that you can't update or delete. Learning to get unstuck from these scenarios is important

To take an application-first approach to DevOps

- Application developers are increasingly being tasked with operational duties

- While learning about IaC, I had a hard time finding in-depth materials covering application development, CI/CD pipelines, automation, and Infrastructure as Code and how these three knowledge domains work together. There are important considerations to make when between a Hello World docker image

- You could probably use another framework with these IaC libraries like Flask or Rails, but for now I'm building these projects with Django first-in-mind

To develop a project I can reference when helping myself and others

- companies and projects that do IaC and CI/CD for the most part have things in private repos for obvious reasons, there isn't any good reason to share this type of code unless you are sharing it with an auditor

- Hopefully, the sample application, IaC, and CI/CD pipelines aren't overly complex. There are more complex examples of open-source companies out there, but their repos have steep learning curves and a lot going on

- People often ask about how to split up IaC deployments and application deployments. I want to be able to use this project to show people how it can be done

To encourage others (specifically Developer Advocates / Developer Relations / Solutions Architects in the CDK, Terraform, and Pulumi communities) to share complete and non-trivial examples of IaC software in use with an actual application.

- There are many ways one could create an "IaC Rosetta Stone" (

public cloud providers x CI/CD providers x IaC toolsis a big number) - This takes a lot of effort and time

I have nothing to sell you

- So many articles about Cloud/DevOps are trying to sell you a tool. Outside of what I consider to be mainstream vendors like GitHub and AWS, there are no products that I'm promoting here

- I'm also not trying to sell anyone on using my IaC packages

- Hopefully, my IaC packages can serve as a helpful reference or starting point

Walk before running

- I want to build up confidence with vanilla use cases before getting too fancy

- With a solid foundation in these tools, I want to learn about some of the more advanced patterns teams are adopting (Pulumi Automation API, Terragrunt for Terraform, self-mutating CDK Pipelines)

12 Factor App, DevOps, and Platform Engineering

- 12 Factor App is great and has guided how I approach both Django application development and IaC library development

- The platformengineering.org community has some good guiding principles

CDK/Terraform/Pulumi terminology

constructs, modules and components

A CDK construct, Terraform module and Pulumi component generally mean the same thing: an abstract grouping of one or more cloud resources.

In this article I will refer to constructs/modules/components as c/m/c for short, and the term stack can generally be used to refer to either a CloudFormation stack, a Pulumi Stack or a Terraform group of resources that are part of a module that has had apply ran against it.

what is a stack?

AWS has a resource type called CloudFormation Stacks, and Pulumi also has a concept of stacks. Terraform documentation doesn't refer to stacks, and instead in Terraform docs use the words "Terraform configuration" to refer to some group of resources that were built using a module.

CDK Constructs and Pulumi Components are somewhat similar, however CDK Constructs map to CloudFormation and the Pulumi components I'm using from the @pulumi/aws package generally map directly to Terraform resources from the AWS Provider (the Pulumi AWS Provider uses much of the same code that the Terraform AWS Provider uses).

verbs

In CDK you synth CDK code to generate CloudFormation templates. You can also run diff to see what changes would be applied during a stack update.

In Terraform you init to download all providers and modules. This is sort of like running npm install in CDK and Pulumi. You then run terraform plan to see the changes that would result. terraform apply does CRUD operations on your cloud resources.

In Pulumi you run pulumi preview to see what changes would be made to a stack. You can use the --diff flag to see the specifics of what would change.

To summarize:

- In CDK you synth CloudFormation and use these templates to deploy stacks made up of constructs. An "app" can contain multiple stacks, and you can deploy one or more stacks in an app at a time

- In Terraform you plan a configuration made up of modules, and then run

terraform applyto build the configuration/stack (discuss.hashicorp.com/t/what-is-a-terraform-stack/31985) - Pulumi: You preview a Pulumi stack made up of components, and then run

pulumi upto build the resources - To tear down a stack in all three tools, you run

destroy

Infrastructure as Code library repos

Let's look at the three repos that I wrote for deploying the same type of 3-tier web application to AWS using ECS Fargate.

- CDK:

cdk-django - Terraform:

terraform-aws-django - Pulumi:

pulumi-aws-django

Language

cdk-django and pulumi-aws-django are both written in TypeScript. terraform-aws-django is written in HCL, a domain specific language created by HashiCorp. The cdk-django is published to both npm and PyPI, so you can use it in JavaScript, TypeScript and Python projects, other languages are supported as well, but you need to write your library in TypeScript so it can be transpiled to other languages using jsii.

My Pulumi library is written in TypeScript and is published to NPM. For now it can only be used in JavaScript and TypeScript projects. There is a way in Pulumi to write in any language and then publish to any other major language, but I haven't done this yet. See this GitHub repo for more information on this.

The HCL is pretty simple when you get used to it. I find that I don't like adding lots of logic in Terraform code because it takes away from the readability of a module. There is a tool called CDKTF which allows you to write HCL Terraform in TypeScript, but I haven't used it yet.

Release management, versioning and publishing

pulumi-aws-django and terraform-aws-django both use release-please for automatically generating a changelog file and bumping versions. release-please is an open source tool from Google that they use to version their Terraform GCP modules. Whenever I push new commits to main, a new PR is created that adds changes to the CHANGELOG.md file, bumps the version of the library in package.json and adds a new git tag (e.g. v1.2.3) based on commit messages.

cdk-django uses projen for maintaining the changelog and bumping versions and publishing to npm. It is popular among developers in the CDK community and is a really awesome tool since it basically uses one file (.projenrc.ts) to configure your entire repo, including files like tsconfig.json, package.json, and even GitHub Action workflows. It has a lot of configuration options, but I'm using it in a pretty simple way. It generates a new release and items to the changelog when I manually trigger a GitHub Action.

These tools are both based on conventional commits to automatically update the Changelog file.

I'm still manually publishing my pulumi-aws-django package from the CLI. I need to add a GitHub Action to do this for me. This and other backlog items are listed at the end of the article!

Makefile, examples and local development

Each repo has a Makefile that includes commands that I frequently use when developing new features or fixing bugs. Each repo has commands for the following:

- synthesizing CDK to CloudFormation / running

terraform plan/ previewing pulumi up for both the base and app stacks - creating/updating an ad hoc base stack called

dev - destroying resources in the ad-hoc base stack called

dev - creating an ad hoc app stack called

alphathat uses resources fromdev - destroying an ad hoc app stack called

alphathat uses resources fromdev - creating/updating a prod base stack called

stage - destroying resources in the prod base stack called

stage - creating a prod app stack using called

stagethat uses resources from thestagebase stack - destroying resources in the prod app stack called

stage

Here's an example of what these commands look like in pulumi-aws-django for prod infrastructure base and app stacks:

prod-base-preview: build

pulumi -C examples/prod/base --stack stage --non-interactive preview

prod-base-up: build

pulumi -C examples/prod/base --stack stage --non-interactive up --yes

prod-base-destroy: build

pulumi -C examples/prod/base --stack stage --non-interactive destroy --yes

prod-app-preview: build

pulumi -C examples/prod/app --stack stage --non-interactive preview

prod-app-preview-diff: build

pulumi -C examples/prod/app --stack stage --non-interactive preview --diff

prod-app-up: build

pulumi -C examples/prod/app --stack stage --non-interactive up --yes

prod-app-destroy: build

pulumi -C examples/prod/app --stack stage --non-interactive destroy --yes

I currently don't have tests for all of these libraries, but for now the most effective way of testing that things are working correctly is to use the c/m/cs to create environments and smoke check the environments to make sure everything works correctly.

Adding unit tests is another item for the backlog.

ad-hoc vs prod

- the last article I wrote was about ad hoc environments. Also known as "on-demand" environments or "preview" environments.

- the motivation for using ad-hoc environments is speed and cost (you can stand up an environment in less time and you share the costs of the base environment, including VPC, ALB, RDS)

- you can completely ignore "ad-hoc" environments and use the "prod" infrastructure for any number of environments (such as dev, QA, RC, stage and prod)

- prod can be used for a production environment and any number of pre-production environments

- multiple environments built with "prod" infrastructure can be configured with a "knobs and dials" (e.g., how big are app and DB instances, how many tasks to run in a service, etc.)

- the "prod" infrastructure should be the same for the "production" environment and the "staging" environment

Directory structure

The directory structures for each repo are all similar with some minor differences.

There are two types of environments: ad-hoc and prod. Within ad-hoc and production, there are two directories base and app.

Each repo has a directory called internal which contain building blocks used by the c/m/cs that are exposed. The contents of the internal directories are not intended to be used by anyone who is using the libraries.

CDK construct library repo structure

~/git/github/cdk-django$ tree -L 4 -d src/

src/

├── constructs

│ ├── ad-hoc

│ │ ├── app

│ │ └── base

│ ├── internal

│ │ ├── alb

│ │ ├── bastion

│ │ ├── customResources

│ │ │ └── highestPriorityRule

│ │ ├── ecs

│ │ │ ├── iam

│ │ │ ├── management-command

│ │ │ ├── redis

│ │ │ ├── scheduler

│ │ │ ├── web

│ │ │ └── worker

│ │ ├── rds

│ │ ├── sg

│ │ └── vpc

│ └── prod

│ ├── app

│ └── base

└── examples

└── ad-hoc

├── app

│ └── config

└── base

└── config

Terraform module library repo structure

~/git/github/terraform-aws-django$ tree -L 4 -d modules

modules

├── ad-hoc

│ ├── app

│ └── base

├── internal

│ ├── alb

│ ├── autoscaling

│ ├── bastion

│ ├── ecs

│ │ ├── ad-hoc

│ │ │ ├── celery_beat

│ │ │ ├── celery_worker

│ │ │ ├── cluster

│ │ │ ├── management_command

│ │ │ ├── redis

│ │ │ └── web

│ │ └── prod

│ │ ├── celery_beat

│ │ ├── celery_worker

│ │ ├── cluster

│ │ ├── management_command

│ │ └── web

│ ├── elasticache

│ ├── iam

│ ├── rds

│ ├── route53

│ ├── s3

│ ├── sd

│ └── sg

└── prod

├── app

└── base

Pulumi component library repo structure

~/git/github/pulumi-aws-django$ tree -L 3 src/

src/

├── components

│ ├── ad-hoc

│ │ ├── README.md

│ │ ├── app

│ │ └── base

│ └── internal

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── alb

│ ├── bastion

│ ├── cw

│ ├── ecs

│ ├── iam

│ ├── rds

│ └── sg

└── util

├── index.ts

└── taggable.ts

Pulumi examples directory

~/git/github/pulumi-aws-django$ tree -L 3 examples/

examples/

└── ad-hoc

├── app

│ ├── Pulumi.alpha.yaml

│ ├── Pulumi.yaml

│ ├── index.ts

│ ├── node_modules

│ ├── package-lock.json

│ ├── package.json

│ └── tsconfig.json

└── base

├── Pulumi.yaml

├── bin

├── index.ts

├── package-lock.json

├── package.json

└── tsconfig.json

CLOC

Let's use CLOC (count lines of code) to compare the lines of code used in the c/m/c of CDK/CloudFormation/Terraform/Pulumi.

cdk-django

~/git/github/cdk-django$ cloc src/constructs/

14 text files.

14 unique files.

0 files ignored.

github.com/AlDanial/cloc v 1.94 T=0.04 s (356.1 files/s, 30040.9 lines/s)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Language files blank comment code

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeScript 13 155 59 908

Python 1 18 8 33

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SUM: 14 173 67 941

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

terraform-aws-django

~/git/github/terraform-aws-django$ cloc modules/

68 text files.

58 unique files.

11 files ignored.

github.com/AlDanial/cloc v 1.94 T=0.15 s (385.9 files/s, 20585.1 lines/s)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Language files blank comment code

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HCL 55 472 205 2390

Markdown 3 7 0 20

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SUM: 58 479 205 2410

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

pulumi-aws-django

~/git/github/pulumi-aws-django$ cloc src/components/

15 text files.

15 unique files.

0 files ignored.

github.com/AlDanial/cloc v 1.94 T=0.11 s (134.5 files/s, 12924.2 lines/s)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Language files blank comment code

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeScript 13 110 176 1119

Markdown 2 6 0 30

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SUM: 15 116 176 1149

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Communities

The CDK, Terraform and Pulumi communities are all great and a lot of people helped when I got stuck on issues writing these libraries. Thank you!

μblog

μblog is a micro blogging application that I have written using Django and Vue.js. Here's a screenshot of the homepage:

It is a pretty simple app. Users can write posts with text and an optional images. Logged in users can write posts and like posts.

Mono-repo structure

It lives in a GitHub mono repo called django-step-by-step. This mono repo contains a few different things:

- backend Django application

- frontend Vue.js application

- IaC code that uses c/m/c from

cdk-django,terraform-aws-djangoandpulumi-aws-django - GitHub Actions workflows for both Infrastructure deployments and application deployments

μblog is the reference application that I deploy to infrastructure created with CDK, Terraform and Pulumi. μblog is meant to represent a generic 12 Factor application that uses:

- gunicorn for a backend API

- Vue.js for a client that consumes the backend API

- celery for async task processing

- celery beat for scheduling tasks

- Postgres for relational data

- Redis for caching and message brokering

- S3 for object storage

- Django admin for a simple admin interface

There is a lot more I could add on μblog. For now I'll just mention that it:

- has a great local development environment (supports both docker-compose and virtual environments)

- demonstrates how to use Django in different ways. It implements the same application using Function Based View and Class Based Views, and implements both a REST API (both with FBV and CBV) and GraphQL.

- GitHub Actions for running unit tests

- k6 for load testing

- contains a documentation site deployed to GitHub pages (made with VuePress) can be found here: https://briancaffey.github.io/django-step-by-step/

Infrastructure Deep Dive

Let's go through each of the c/m/cs used in the three libraries. I'll cover some of the organizational decisions, dependencies and differences between how things are done between CDK, Terraform and Pulumi.

I'll first talk about the two stacks used in ad hoc environments: base and app. Then I'll talk about the prod environments which are also composed of base and app stacks.

Keep in mind that there aren't that many differences between the ad hoc environment base and app stacks and the prod environment app and base stacks. A future optimization could be to use a single base and app stack, but I think there is a trade-off between readability and DRYness of infrastructure code, especially with Terraform. In general I try to use very little conditionals and logic with Terraform code. It is much easier to have dynamic configuration in CDK and Pulumi, and probably also for other tools like CDKTF (that I have not yet tried).

Splitting up the stacks

While it is possible to put all resources in a single stack with both Terraform, CDK and Pulumi, it is not recommended to do so.

- Terraform enables this with outputs and

terraform_remote_state - Pulumi encourages the use of micro stacks

- CDK has an article on how to create an app with multiple stacks

My design decision was to keep things limited to 2 stacks. Later on it would be interesting to try splitting out another stack.

Also, on-demand environments really lends itself to stacks that are split up.

In the section "Passing unique identifiers", the CDK recommends that we keep the two stacks in the same app. In Terraform and Pulumi, each stack environment is in its own app.

There is a balance to be found between single stacks vs micro stacks. Both the base and app c/m/cs could be split out further. For example, the base c/m/cs could be split into networking and rds. The app stack could be split into different ECS services so that their infrastructure can be deployed independently, like cluster, backend and frontend. The more resources that a stack has, the longer it takes to deploy and the more risky it gets, but adding lots of stacks can add to mental overhead, and pipeline complexity. Each tool has ways of dealing with these complexities (CDK Pipelines, Terragrunt, Pulumi Automation API), but I won't be getting into any of these options in this article. I would like to try these out and share in a future article.

My rules of thumbs are:

- single stacks are bad because you don't want to put all your eggs in one basket, however your IaC tool should give you confidence about what is going to change when you try to make a change

- Lots of small stacks can cause overhead and make things more complex than they need to be

Ad hoc base overview

Here's an overview of the resources used in an ad hoc base environment.

- (Inputs)

- (Optional environment configs)

- VPC and Service Discovery

- S3

- Security Groups

- Load Balancer

- RDS

- Bastion Host

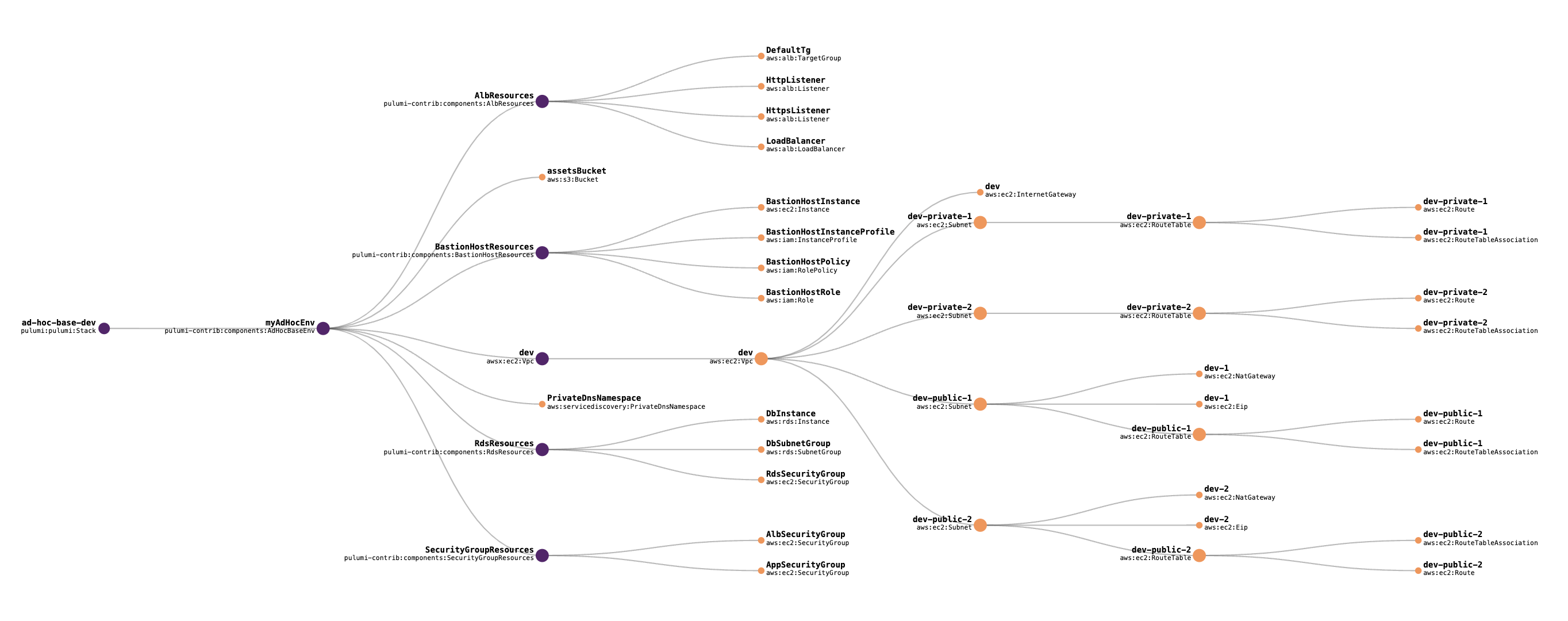

Visualization

Here's a dependency graph showing all of the resources in ad hoc base stack. This can be found on the Resources tab of the ad hoc base stack in the Pulumi console.

Inputs

There are only two required inputs for the ad hoc base stack

- ACM certificate ARN

- Domain Name

I store these values in environment variables for the pipelines in CDK, Terraform and Pulumi. When running pipelines from my local environment, they are exported in my shell before running deploy/apply/up or synth/plan/preview.

VPC

The VPC is the first resource that is created as part of the base stack. There official, high-level constructs in each IaC tool for building VPCs and all related networking resources.

awsxhas a VPC moduleterraform-aws-vpcmodule- L2 VPC Construct in CDK

The setting in the Terraform VPC module one_nat_gateway_per_az = false doesn't seem to exist on the awsx.ec2.Vpc module. This will add to cost savings since it will use 1 NAT Gateway instead of 2 or 3.

Security Groups

Pulumi and Terraform can be used in a similar way to define security groups. CDK has a much more concise option for defining ingress and egress rules for security groups.

const albSecurityGroup = new SecurityGroup(scope, 'AlbSecurityGroup', {

vpc: props.vpc,

});

albSecurityGroup.addIngressRule(Peer.anyIpv4(), Port.tcp(443), 'HTTPS');

albSecurityGroup.addIngressRule(Peer.anyIpv4(), Port.tcp(80), 'HTTP');

Load Balancer Resources

There's not much to comment on here. In each library I have resource group that defines the following:

- Application Load Balancer

- A default target group

- An HTTP listener that redirects to HTTPS

- An HTTPS listener with a default "fixed-response" action

Properties from these resources are used in the "app" stack to build listener rules for ECS services that are configured with load balancers, such as the backend and frontend web services.

Ad hoc app environments all share a common load balancer from the base stack that they use.

RDS Resources

All three libraries have the RDS security group and Subnet Group in the same c/m/c as the RDS instance. The SG and DB Subnet group could alternatively be grouped closer to the other network resources.

Currently the RDS resources are part of the "base" stack for each library. A future optimization may be to break the RDS instance out of the "base" stack and put it in its own stack. The "RDS" stack would be dependent on the "base" stack, and then "app" stack would then be dependent on both the "base" stack and the "RDS" stack. More stacks isn't necessarily a bad thing, but for my initial implementation of these libraries I have decided to keep the "micro stacks" approach limited to only 2 stacks for an environment.

The way that database secrets are handled is another difference between CDK and Terraform and Pulumi. I am currently "hardcoding" the RDS password for Terraform and Pulumi, and in CDK I am using a Secrets Manager Secret for the database credential.

const secret = new Secret(scope, 'dbSecret', {

secretName: props.dbSecretName,

description: 'secret for rds',

generateSecretString: {

secretStringTemplate: JSON.stringify({ username: 'postgres' }),

generateStringKey: 'password',

excludePunctuation: true,

includeSpace: false,

},

});

In the DatabaseInstance props we can then use this secret like so:

credentials: Credentials.fromSecret(secret),

In the application deployed with CDK, I use a Django settings module package that uses a package called aws_secretsmanager_caching to get and cache the secrets manager secret for the database, whereas in the apps deployed with Terraform and Pulumi I read in the password from an environment variable.

The Terraform and Pulumi database instance arguments simply accept a password field. This will be another item for the backlog for Terraform and Pulumi. The randompassword and secretversion components can be used to do this.

Bastion Host

There are two main use cases for the bastion host in ad-hoc environments.

- When creating a new ad hoc app environment, the bastion host is used to create a new database called

{ad-hoc-env-name}-dbthat the new ad hoc environment will use. (There might be another way of doing this, but using a bastion host is working well for now). - If you using a database management tool on you local machine like DBeaver, the bastion host can help you connect to the RDS instance in a private subnet. The bastion host instance is configured to run a service that forwards traffic on port 5432 to the RDS instance. If you port forward from your local machine to the bastion host on port 5432, you can connect RDS by simple connecting to

localhost:5432on your local machine.

You don't need to manage SSH keys since you connect to the instance in a private subnet using SSM:

aws ssm start-session --target $INSTANCE_ID

Outputs

Here are the outputs for the ad hoc base stack used in Terraform and Pulumi:

- vpc_id

- assets_bucket_name

- private_subnet_ids

- app_sg_id

- alb_sg_id

- listener_arn

- alb_dns_name

- task_role_arn

- execution_role_arn

- rds_address

In CDK, the stack references in the app stack don't reference the unique identifiers from the base stack (such as the VPC id or bastion host instance id), but instead they reference the properties of the stack which have types like Vpc and RdsInstance. More on this later in the following section Passing data between stacks.

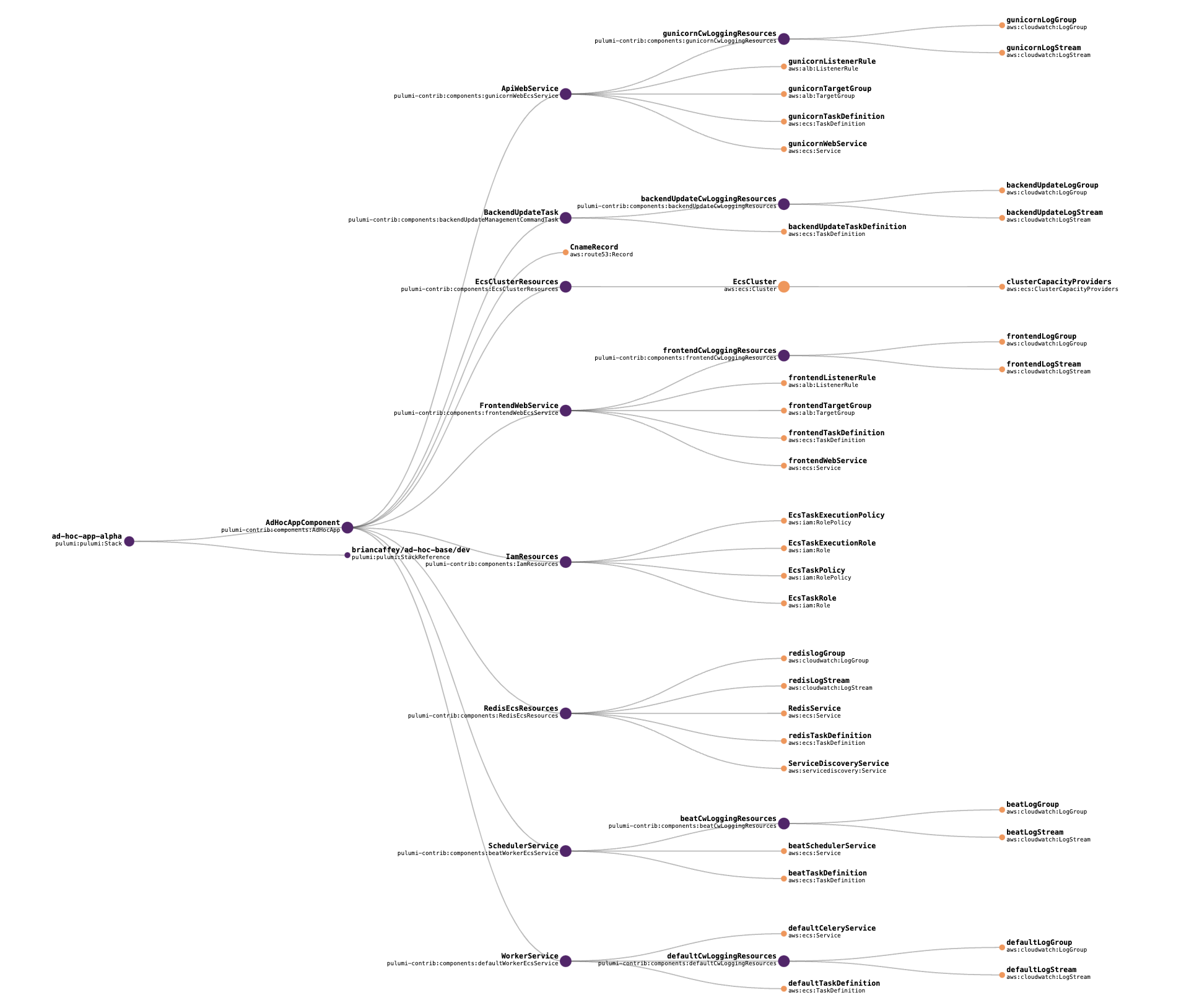

Ad hoc app overview

The ad hoc app is an group of resources that powers an on-demand environment that is meant to be short lived for testing, QA, validation, demos, etc.

This visualization shows all of the resources in the ad hoc app stack. It also comes from the Pulumi console.

ECS Cluster

- This is a small component that defines both ECS Cluster and the default capacity providers

- It defaults to not using

FARGATE_SPOT; ad hoc environments do useFARGATE_SPOTfor cost savings

NOTE: defaultCapacityProviderStrategy on cluster not currently supported. (link)

Shared environment variables

The backend containers should all have the same environment variables, so I define them once in the app stack and pass these into the service resource c/m/cs.

- I struggled to get this right in pulumi. A lot of Pulumi examples used

JSON.stringifyfor containerDefinitions in task definitions. I was able to get help from the Pulumi Slack channel; someone recommended that I usepulumi.jsonStringifywhich was added in a relatively recent version ofpulumi/pulumi. - CDK allows you to declare environment variables for a containerDefinition like

{ FOO: "bar" } - Pulumi and Terraform require that values are passed like

{ name: "FOO", value: "bar"} - You could transform

{ FOO: "bar" }into the name/value format, but I didn't bother to do this - extra env vars in Terraform to allow for dynamically passing extra environment variables, and I used the

concatfunction to add these to the list of default environment variables.

Here's what the code looks like for joining extra environment variables to the default environment variables:

// CDK

if (extraEnvVars) {

environmentVariables = { ...extraEnvVars, ...environmentVariables };

}

# terraform

env_vars = concat(local.env_vars, var.extra_env_vars)

// Pulumi

if (extraEnvVars) {

envVars = envVars.apply(x => x.concat(extraEnvVars!))

}

Route53 Record

This is pretty straightforward in each library. Each ad hoc environment gets a Route 53 record, and listener rules for the web services (Django and Vue.js SPA) match on a combination of the host header and path patterns.

This part is pretty opinionated in that it assumes you want to host the frontend and backend services on the same URL. For example, requests matching example.com/api/* are routed to the backend API and all other requests matching example.com/* are routed to the frontend service.

Redis

I go into more depth about why I run a Redis instance in an ECS service in my other article. This is only for the ad hoc environments. Production environments are configured with ElastiCache running Redis.

I decided to not make this service use any persistent storage. It may be a good idea to not use FARGATE_SPOT for this service, since restarts to the redis service could cause issues in ad hoc environments. For example, you may get a lot of celery errors in ad hoc environments if redis is not reachable.

Web Service

The web service is what defines the main Django application as well as the frontend website (JavaScript SPA or SSR site). I designed the Web Service resources group to be able to support both traditional Django apps (powered by templates), or for Django apps that service only a limited number of endpoints. This c/m/c has an input parameter called pathPatterns which determines which paths it serves. For example, the API container may serve traffic for /api/* and /admin/* only, or it may want to serve all traffic (/*).

The way I use these components in ad hoc and prod environments is heavily opinionated in that:

- it assumes that the frontend SPA/SSR site should have a lower priority rule than the backend service and should route request paths matching

/*, while the backend service routes requests for a specific list of path patterns (/api/*,/admin/*,/graphql/*, etc.).

You may want Django to handle most of your routes and 404 pages, in which case you would want the SPA to only handle requests matching certain paths. This would require some more consideration and careful refactoring.

Celery

- The reason for having a celery service is to be able to have potentially multiple workers that scale independently

- I use the same Pulumi component for both works and schedulers

The terminology for this resource group could be better. Celery is one of many options for running async task workers, so it should probably be called something like AsyncWorker across the board rather than using the term celery.

Management Command

- Defines a task that can be used to run commands like

collectstaticandmigrate - These tasks are ran both after the initial

appstack deployment and before rolling application upgrades

In my Django app I have a single management command that calls migrate and collectstatic and runs them in the same process one after another. This management command could also be used for clearing caches during updates, loading fixtures, etc.

One other thing to note about this c/m/c is that it outputs a complete script that can be used in GitHub Actions (or on your CLI when testing locally) that does the following:

- saves the

STARTtimestamp - runs the task with the required settings

- waits for the task to complete

- saves the

ENDtimestamp - collects the logs for the task between

STARTandENDand prints them tostdout

Here's an example of what the script looks like in Pulumi:

const executionScript = pulumi.interpolate`#!/bin/bash

START_TIME=$(date +%s000)

TASK_ID=$(aws ecs run-task --cluster ${props.ecsClusterId} --task-definition ${taskDefinition.arn} --launch-type FARGATE --network-configuration "awsvpcConfiguration={subnets=[${props.privateSubnetIds.apply(x => x.join(","))}],securityGroups=[${props.appSgId}],assignPublicIp=ENABLED}" | jq -r '.tasks[0].taskArn')

aws ecs wait tasks-stopped --tasks $TASK_ID --cluster ${props.ecsClusterId}

END_TIME=$(date +%s000)

aws logs get-log-events --log-group-name ${cwLoggingResources.cwLogGroupName} --log-stream-name ${props.name}/${props.name}/\${TASK_ID##*/} --start-time $START_TIME --end-time $END_TIME | jq -r '.events[].message'

`;

this.executionScript = executionScript;

In GitHub Actions we get this command as a stack output, save it to a file, make it executable and then run it. This is what it looks like with CDK as a CloudFormation stack output:

- name: "Run backend update command"

id: run_backend_update

run: |

# get the script from the stack output with an output key that contains the string `backendUpdate`

BACKEND_UPDATE_SCRIPT=$(aws cloudformation describe-stacks \

--stack-name $AD_HOC_APP_NAME \

| jq -r '.Stacks[0].Outputs[]|select(.OutputKey | contains("backendUpdate")) | .OutputValue' \

)

echo "$BACKEND_UPDATE_SCRIPT" > backend_update_command.sh

cat backend_update_command.sh

sudo chmod +x backend_update_command.sh

./backend_update_command.sh

Passing data between stacks

Pulumi uses stack references, Terraform uses remote state and CDK uses Stack Outputs or Stack References.

Here's what this looks like in Terraform

data "terraform_remote_state" "this" {

backend = "local"

config = {

path = "../base/terraform.tfstate"

}

}

module "main" {

source = "../../../modules/ad-hoc/app"

vpc_id = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.vpc_id

assets_bucket_name = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.assets_bucket_name

private_subnet_ids = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.private_subnet_ids

app_sg_id = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.app_sg_id

alb_sg_id = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.alb_sg_id

listener_arn = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.listener_arn

alb_dns_name = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.alb_dns_name

service_discovery_namespace_id = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.service_discovery_namespace_id

rds_address = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.rds_address

domain_name = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.domain_name

base_stack_name = data.terraform_remote_state.this.outputs.base_stack_name

region = var.region

}

In CDK:

const baseStack = new Stack(app, 'ExampleAdHocBaseStack', { env, stackName: adHocBaseEnvName });

baseStack.node.setContext('config', adHocBaseEnvConfig);

const appStack = new Stack(app, 'ExampleAdHocAppStack', { env, stackName: adHocAppEnvName });

appStack.node.setContext('config', adHocAppEnvConfig);

const adHocBase = new AdHocBase(baseStack, 'AdHocBase', { certificateArn, domainName });

const addHocApp = new AdHocApp(appStack, 'AdHocApp', {

baseStackName: adHocBaseEnvName,

vpc: adHocBase.vpc,

alb: adHocBase.alb,

appSecurityGroup: adHocBase.appSecurityGroup,

serviceDiscoveryNamespace: adHocBase.serviceDiscoveryNamespace,

rdsInstance: adHocBase.databaseInstance,

assetsBucket: adHocBase.assetsBucket,

domainName: adHocBase.domainName,

listener: adHocBase.listener,

});

and in Pulumi:

const stackReference = new pulumi.StackReference(`${org}/ad-hoc-base/${environment}`)

const vpcId = stackReference.getOutput("vpcId") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const assetsBucketName = stackReference.getOutput("assetsBucketName") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const privateSubnets = stackReference.getOutput("privateSubnetIds") as pulumi.Output<string[]>;

const appSgId = stackReference.getOutput("appSgId") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const albSgId = stackReference.getOutput("albSgId") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const listenerArn = stackReference.getOutput("listenerArn") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const albDnsName = stackReference.getOutput("albDnsName") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const serviceDiscoveryNamespaceId = stackReference.getOutput("serviceDiscoveryNamespaceId") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const rdsAddress = stackReference.getOutput("rdsAddress") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const domainName = stackReference.getOutput("domainName") as pulumi.Output<string>;

const baseStackName = stackReference.getOutput("baseStackName") as pulumi.Output<string>;

// ad hoc app env

const adHocAppComponent = new AdHocAppComponent("AdHocAppComponent", {

vpcId,

assetsBucketName,

privateSubnets,

appSgId,

albSgId,

listenerArn,

albDnsName,

serviceDiscoveryNamespaceId,

rdsAddress,

domainName,

baseStackName

});

CLI scaffolding

CDK and Pulumi have some good options for how to scaffold a project.

- Pulumi has

pulumi new aws-typescriptamong lots of other options (runpulumi new -lto see over 200 project types). I used this to create the library itself, the examples and the pulumi projects that I use indjango-step-by-stepthat consume the library. - CDK has

projenCLI commands which can help set up either library code or project code - The major benefits of these tools is setting up

tsconfig.jsonandpackage.jsoncorrectly - Terraform is so simple that it doesn't really need tooling for scaffolding

Best practices

For terraform-aws-django, I tried to follow the recommendations from terraform-best-practices.com which helped me a lot with things like consistent naming patterns and directory structures. For example:

- use the name

thisfor resources in a module where that resource is the only resource of its type

CDK and Pulumi lend themselves to more nesting and abstractions because they can be written in more familiar programming languages with better abstractions, functions, loops, classes, etc., so there are some differences in directory structure of my libraries when comparing Terraform to both CDK and Pulumi.

For Pulumi and CDK, I mostly tried to follow along with recommendations from their documentation and example projects. While working with Pulumi I struggled a bit with the concepts of Inputs, Outputs, pulumi.interpolate, apply(), all() and the differences between getX and getXOutput. There is a little bit of a learning curve here, but the documentation and examples go a long way in showing how to do things the right way.

Environment configuration

Environment configuration allows for either a base or app stack to be configured with non-default values. For example:

- you may decide to start a new base environment but you want to provision a powerful database instance class and size. You would change this using environment configuration

- You might want to create an ad hoc app environment but you need it to include some special environment variables, you could set these in environment config.

In the examples above, our IaC can optionally take environment configuration values that overwrite default values, or extend default values.

- Pulumi defines environment-specific config in files called

Pulumi.{env}.yaml(Pulumi article on configuration) - Terraform uses

{env}.tfvarsfor this type of configuration - CDK has several options for this type of configuration (

cdk.context.json, extending stack props, etc.)

For CDK I have been using setContext and the tryGetContext method:

setContext needs to be set on the node before any child nodes are added:

const baseStack = new Stack(app, 'ExampleAdHocBaseStack', { env, stackName: adHocBaseEnvName });

baseStack.node.setContext('config', adHocBaseEnvConfig);

const appStack = new Stack(app, 'ExampleAdHocAppStack', { env, stackName: adHocAppEnvName });

appStack.node.setContext('config', adHocAppEnvConfig);

And the config objects are read from JSON files like this:

var adHocBaseEnvConfig = JSON.parse(fs.readFileSync(`src/examples/ad-hoc/base/config/${adHocBaseEnvName}.json`, 'utf8'));

var adHocAppEnvConfig = JSON.parse(fs.readFileSync(`src/examples/ad-hoc/app/config/${adHocAppEnvName}.json`, 'utf8'));

The context can be used in constructs like this:

const extraEnvVars = this.node.tryGetContext('config').extraEnvVars;

Pulumi has similar functions for getting context values, here's an example of how I get extra environment variables for app environments using Pulumi's config:

interface EnvVar {

name: string;

value: string;

}

let config = new pulumi.Config();

let extraEnvVars = config.getObject<EnvVar[]>("extraEnvVars");

In my Pulumi.alpha.yaml file I have the extraEnvVars set like this:

config:

aws:region: us-east-1

extraEnvVars:

- name: FOO

value: BAR

- name: BIZ

value: BUZ

I haven't done too much with configuration, but it seems like the right place to build out all of the dials and switches for optional settings in stack resources that you want people to be able to change in their ad hoc environments, or that you want to set per "production" environment (QA, stage, prod, etc.)

Local development

Using the Makefile targets in each library repo, my process for developing c/m/cs involves making code changes followed by Makefile targets that preview/plan/diff against my AWS account, then running deploy/apply/up and waiting for things to finish deploying. Once I can validate that things are looking correct in my account, I run the destroy command and make sure that all of the resources are removed successfully. RDS instances can take up to 10 minutes to create, which means that the base stack takes some time to test. The app environment is able to be spun up quickly, but it can sometimes get stuck and take some time to delete services.

Here are some sample times for deploying ad hoc stacks with CDK.

# CDK ad hoc base deployment time

✅ ExampleAdHocBaseStack (dev)

✨ Deployment time: 629.64s

# CDK ad hoc app deployment time

✅ ExampleAdHocAppStack (alpha)

✨ Deployment time: 126.62s

Here is an example of what the pulumi preview commands shows for the ad-hoc base stack:

# Pulumi preview

~/git/github/pulumi-aws-django$ pulumi -C examples/ad-hoc/base --stack dev preview

Previewing update (dev)

View Live: https://app.pulumi.com/briancaffey/ad-hoc-base/dev/previews/718625b2-48f5-4ef4-8ed4-9b2694fda64a

Type Name Plan

+ pulumi:pulumi:Stack ad-hoc-base-dev create

+ └─ pulumi-contrib:components:AdHocBaseEnv myAdHocEnv create

+ ├─ pulumi-contrib:components:AlbResources AlbResources create

+ │ ├─ aws:alb:TargetGroup DefaultTg create

+ │ ├─ aws:alb:LoadBalancer LoadBalancer create

+ │ ├─ aws:alb:Listener HttpListener create

+ │ └─ aws:alb:Listener HttpsListener create

+ ├─ pulumi-contrib:components:BastionHostResources BastionHostResources create

+ │ ├─ aws:iam:Role BastionHostRole create

+ │ ├─ aws:iam:RolePolicy BastionHostPolicy create

+ │ ├─ aws:iam:InstanceProfile BastionHostInstanceProfile create

+ │ └─ aws:ec2:Instance BastionHostInstance create

+ ├─ pulumi-contrib:components:RdsResources RdsResources create

+ │ ├─ aws:rds:SubnetGroup DbSubnetGroup create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:SecurityGroup RdsSecurityGroup create

+ │ └─ aws:rds:Instance DbInstance create

+ ├─ pulumi-contrib:components:SecurityGroupResources SecurityGroupResources create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:SecurityGroup AlbSecurityGroup create

+ │ └─ aws:ec2:SecurityGroup AppSecurityGroup create

+ ├─ aws:s3:Bucket assetsBucket create

+ ├─ awsx:ec2:Vpc dev create

+ │ └─ aws:ec2:Vpc dev create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:InternetGateway dev create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:Subnet dev-private-1 create

+ │ │ └─ aws:ec2:RouteTable dev-private-1 create

+ │ │ ├─ aws:ec2:RouteTableAssociation dev-private-1 create

+ │ │ └─ aws:ec2:Route dev-private-1 create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:Subnet dev-private-2 create

+ │ │ └─ aws:ec2:RouteTable dev-private-2 create

+ │ │ ├─ aws:ec2:RouteTableAssociation dev-private-2 create

+ │ │ └─ aws:ec2:Route dev-private-2 create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:Subnet dev-public-1 create

+ │ │ ├─ aws:ec2:RouteTable dev-public-1 create

+ │ │ │ ├─ aws:ec2:RouteTableAssociation dev-public-1 create

+ │ │ │ └─ aws:ec2:Route dev-public-1 create

+ │ │ ├─ aws:ec2:Eip dev-1 create

+ │ │ └─ aws:ec2:NatGateway dev-1 create

+ │ └─ aws:ec2:Subnet dev-public-2 create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:RouteTable dev-public-2 create

+ │ │ ├─ aws:ec2:RouteTableAssociation dev-public-2 create

+ │ │ └─ aws:ec2:Route dev-public-2 create

+ │ ├─ aws:ec2:Eip dev-2 create

+ │ └─ aws:ec2:NatGateway dev-2 create

+ └─ aws:servicediscovery:PrivateDnsNamespace PrivateDnsNamespace create

Outputs:

albDnsName : output<string>

albSgId : output<string>

appSgId : output<string>

assetsBucketName : output<string>

baseStackName : "dev"

bastionHostInstanceId : output<string>

domainName : "example.com"

listenerArn : output<string>

privateSubnetIds : output<string>

rdsAddress : output<string>

serviceDiscoveryNamespaceId: output<string>

vpcId : output<string>

Resources:

+ 44 to create

Running infrastructure pipelines in GitHub Actions

I don't currently have GitHub Actions working for all tools in all environments, this part is still a WIP but is working at a basic level. Another item for the backlog!

In the .github/workflows directory of the django-step-by-step repo, I will have the following 2 * 2 * 2 * 3 = 24 pipelines for running infrastructure as code pipelines:

{ad_hoc,prod}_{base,app}_{create_update,destroy}_{cdk,terraform,pulumi}.yml

- For CDK I'm using CDK CLI commands

- For Terraform I'm also using terraform CLI commands

- For Pulumi I'm using the official Pulumi GitHub Action

Pulumi has a great article about how to use their official GitHub Action. This action calls the Pulumi CLI under the hood with all of the correct flags.

The general pattern that all of these pipelines use is:

- Do a synth/plan/preview, and upload the synth/plan/preview file to an artifact

- Pause and wait on manual review of the planned changes

- download the artifact and run deploy/apply/up against it, or optionally cancel the operation if the changes you see in the GitHub Actions pipeline logs are not what you expected.

I do this by having two jobs in each GitHub Action: one for synth/plan/preview and one for deploy/apply/up.

The job for deploy/apply/up includes an environment that is configured in GitHub to be a protected environment that requires approvals. Even if you are the only approver (which I am on this project), it is the easiest and safest way preview infrastructure changes before they happen. If you see something in the plan and it isn't what you wanted to change, you cancel the job.

Application deployments

- There are two GitHub Actions pipelines for deploying the frontend and the backend. Both of these pipelines run bash scripts that call AWS CLI commands to perform rolling updates on all of the services used in the application (frontend, API, workers, scheduler)

- The backend deployment script runs database migrations, the

collectstaticcommand and any other commands needed to run before the rolling update starts (clearing the cache, loading fixtures, etc.) - What is important to note here is that application deployments are not dependent on the IaC tool we use. Since we are tagging things consistently across CDK, Terraform and Pulumi, we can look up resources by tag rather than getting "outputs" of the app stacks.

Interacting with AWS via IaC

- CDK interacts directly with CloudFormation (and custom resources which allow for running arbitrary SDK calls and lambda functions) and provides L1, L2 and L3 constructs which offer different levels of abstraction over CloudFormation.

- Terraform has the AWS Provider and the

terraform-aws-modules. - Pulumi has AWS Classic (

@pulumi/aws) provider andAWSx(Crosswalk for Pulumi) library andaws_nativeprovider.

aws_native"manages and provisions resources using the AWS Cloud Control API, which typically supports new AWS features on the day of launch."

aws_native looks like a really interesting option, but it is currently in public preview so I have not decided to use it. I am using the AWSx library only for my VPC and associated resources, everything else uses the AWS Classic provider.

For CDK I use mostly L2 constructs and some L1 constructs.

Fot Terraform I use the VPC from the terraform-aws-modules, and everything else uses the AWS Terraform Provider.

What I did not put in IaC

- ECR (Elastic Container Registry)

- ACM (Amazon Certificate Manager)

- (Roles used for deployments)

I created the Elastic Container Registry backend and frontend repos manually in the AWS Console. I also manually requested an ACM certificate for *.mydomain.com for the domain that I use for testing that I purchased through Route53 domains.

I currently am using another less-than best practice of using Administrative Credentials stored in GitHub secrets. The better approach here is to make roles for different pipelines and use OIDC to authenticate instead of storing credentials. This is another good item for the backlog.

Tagging

- Terraform and CDK both make it easy to automatically tag all resources in a stack

- It is possible to do this in Pulumi, but you need to write a little bit of code.

- https://www.pulumi.com/blog/automatically-enforcing-aws-resource-tagging-policies/

- https://github.com/joeduffy/aws-tags-example/tree/master/autotag-ts

- Tagging is important since I look up resources by tag in GitHub Actions pipelines (for example, the Bastion Host is looked up by tag)

- Automatically tagging resources works through stack transformations are unique to Pulumi

Smoke checking application environments

Here's the list of things I check when standing up an application environment:

- Run the init/tsc, synth/plan/preview and deploy/apply/up commands successfully

- Access the bastion host (

make aws-ssm-start-session) - Run ECSExec to access a shell in a backend container (

make aws-ecs-exec) - Test database connectivity (

python manage.py showmigrations) - Run the migrations (

python manage.py migrate) - Run collectstatic (

python manage.py collectstatic) - Visit the site (

alpha.example.com) - Publish a blog post

- Publish a blog post with an image

- Check celery worker logs for successfully complete scheduled tasks

- Trigger an autoscaling event by running k6 load tests against an environment

- Optionally deploy another backend or frontend image tag using the GitHub Actions pipelines for backend and frontend updates

- Destroy the app stack

- Destroy the base stack

Backlog and next steps

Here are some of the next things I'll be working on in these project, roughly in order of importance:

- Introduce manual approvals in GitHub Actions for all deployments and allow for the previewing or "planning" before proceeding with an live operations in infrastructure pipelines

- Switch to using OIDC for AWS authentication from GitHub Actions and remove AWS secrets from GitHub

- Show how to do account isolation (different accounts for prod vs pre-prod environments)

- GitHub Actions deployment pipeline for publishing

pulumi-aws-djangopackage - Complete all GitHub Action deployment pipelines for base and app stacks (both ad hoc and prod)

- For Pulumi and Terraform, use a Secrets Manager secret for the database instead of hardcoding it. Use the

randomfunctions to do this - Refactor GitHub Actions and make them reusable across different projects

- Writing tests for Pulumi and CDK. Figure out how to write tests for Terraform modules

- Use graviton instances and have the option to select between different architectures

- Standardize all resources names across CDK, Terraform and Pulumi

- The Pulumi components that define the resources associated with each ECS service are not very dry

- Interfaces could be constructed with inheritance (base set of properties that is extended for different types of services)

- Fix the CDK issue with priority rule on ALB listeners. I need to used a custom resource for this which is currently a WIP. Terraform and Pulumi look up the next highest listener rule priority under the hood, so you are not required to provide it, but CDK requires it, which means that you can't do ad hoc environments in CDK without a custom resource that looks up what the next available priority number is.

- Make all three of the libraries less opinionated. For example, the celery worker and scheduler should be optional and the frontend component should also be optional

- experiment with using a frontend with SSR. This is supported by Quasar, the framework I'm currently using to build my frontend SPA site

If you want to get involved or help with any of the above, please let me know!

Conclusion

I first started out with IaC following this project aws-samples/ecs-refarch-cloudformation (which is pretty old at this point) and wrote a lot of CloudFormation by hand. The pain of doing that lead me to explore the CDK with Python. I learned TypeScript by rewriting the Python CDK code I wrote in TypeScript. I later worked with a team that was more experienced in Terraform and learned how to use that. I feel like Pulumi takes the best of the two tools and has a really great developer experience. There is a little bit of a learning curve with Pulumi, and you give up some of the simplicity of Terraform.