Python, Vue, Chinese-LLaMA-2 and The Three-Body Problem

Last updated November 23, 2023

tl;dr

This articles brings together several of my interest, both old and new:

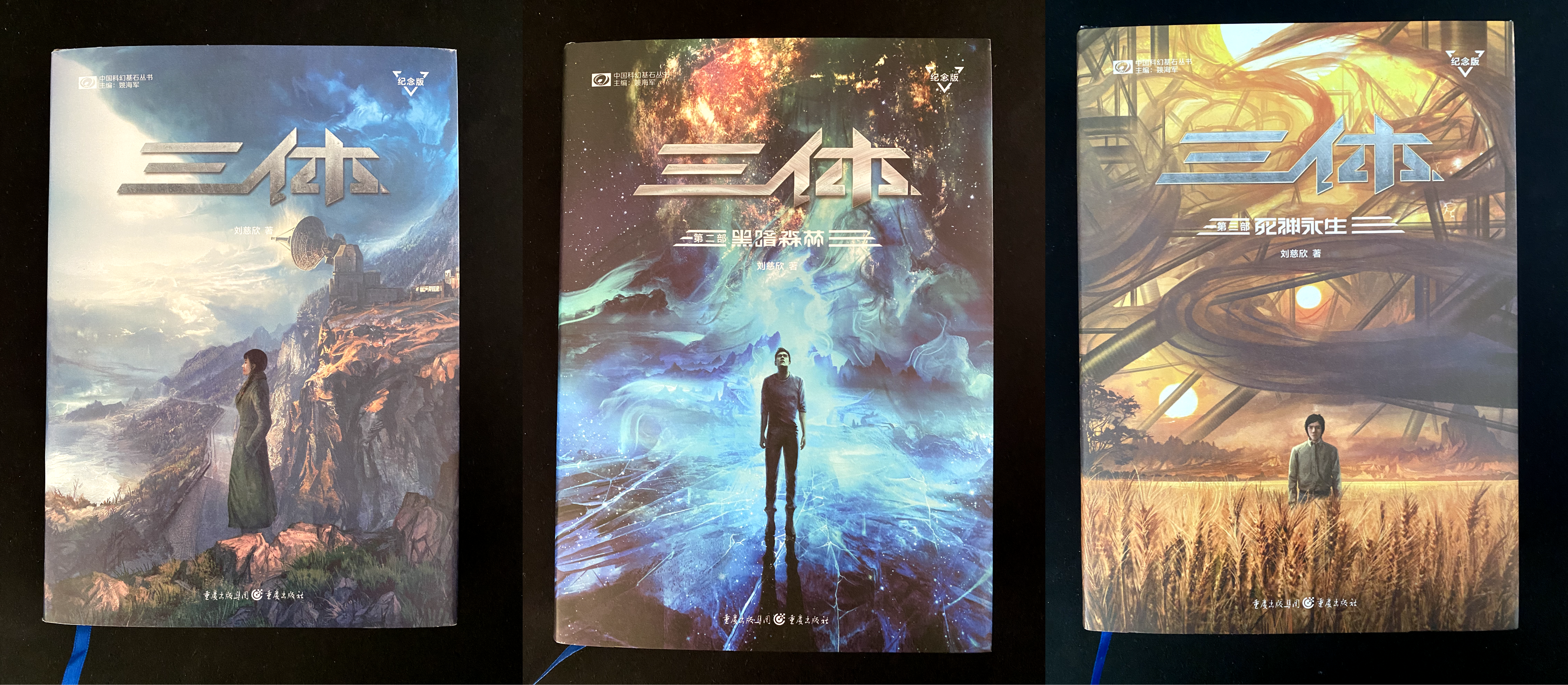

- The Sci-Fi book series 'Three-Body Problem' by Liu Cixun

- Chinese language

- NLP techniques

- Large Language Models (LLMs)

- Stable Diffusion

- Data visualization and 3D graphics

- Mathematics

- NVIDIA / CUDA

This is a linguistic, artistic and computational experiment with the two big AI algorithms of 2023: large language models (LLMs) and Stable Diffusion. I used the leading open-source LLMs from China’s tech sector to translate and summarize the text of Chinese author Liu Cixin’s award-winning science fiction novel: The Three-Body Problem. The book's storyline is based on a simple yet elusive problem from classical physics: predicting the movement of three gravitationally-attracted objects in space. I generated code for simulations and visualizations of this physics problem to present my own solutions to the three-body problem based on parallel computation. I also used Stable Diffusion to portray the imaginitive solutions to the three-body physics problem from one of the book’s main settings: an immersive virtual-reality game that spans centries of world history.

I also share some of my experiences in China as an exchange student and research manager in the renewable energy technology sector. I wrote this article in English and translated it into Chinese using the same large language models I used to translate the Chinese text of the sci-fi novel into English. Warning: this article contains spoilers for the first book in the trilogy!

Back story

A few months ago my company announced that another round of layoffs was to come the following week. I'm on an engineering team that had already been impacted by a few rounds of layoffs in the past year, and I was expecting to be let go. On an impulse I bought a book at the top of my reading list from Amazon: "Three-Body Problem". It is an award-winning Sci-Fi trilogy written by Liu Cixin, a Chinese computer engineer who started writing the book as a series of essays that were published in China's "World of Sci-Fi" magazine.

I started learning Chinese in college, adding a major in Chinese Language to the mathematics major I decided on in my freshman year after taking vector calculus and linear algebra. In my sophmore year I did a semester abroad at Fudan University's International Cultural Exchange School. In 2007, living and studying Chinese in Shanghai as a 19 year old American was a really fun time. I was placed in an advanced-level course with a diverse group of students where English was not the lowest common linguistic denominator. We had a demanding cirriculum that emphasized reading, listening and speaking Chinese, but most of the language learning came through extracirricular activities: exploring Shanghai's food scene, bartering with vendors at the fabric markets, late night clubbing, walking around the Bund and the French Concession and chatting with my taxi cab drivers. It is hard to imagine how I did this without an iPhone, but I was able to get pretty far with an old Nokia 3310.

At the end of one night of particularly heavy drinking, some of my classmates and I dropped in on an wangba (internet cafe) before heading back to the international dorm. Chinese internet cafes in 2007 were an expansive underground dens of computers, monitors, MMORPGs, FPSs, cigarets, and on-demand instant noodles delivered directly to your seat through an app on the desktop. That night our game of choice was Counter-Strike. In one of the lowest points of my gaming career, my classmates and I were crushed by our Chinese counterterrorist opponent.

My favorite memory of that semester at Fudan University was travelling on an epic over-night sleeper train from Shanghai to Guangxi province with a school-sponsored class trip to see Guilin. Multiple games of sam-yuk-gu (3-6-9) ran in parallel across the matrix of 3-by-2 sleeper car bunk beds lining the train car like workloads distributed across multiple GPU cores. The rules of 3-6-9 are simple: a group of people go around in a circle counting up from 1. If your number contains a 3, 6 or 9, you clap once for each occurance of the number instead of saying your number. The first person to break the rules takes a drink. Then repeat indefinitely. The next morning we all boarded a boat cruise in a daze to see the Lijiang river's stunning limestone peaks featured on the 20 yuan note:

My second job after college took me back to China where I specialized in the technologies, policies and applications of large scale battery projects as a research manager for China's energy storage industry association. The job exposed me to the power industry and cutting-edge battery projects, and also sharpened my technical Chinese as I was frequently reading, translating in a bi-linguagl environment. It was fun I didn't realize it at the time, but that job was great preperation for reading Chinese Sci-Fi novels.

My first introduction to the 'Three-Body Problem' book came from one of my best friends from college. He lived at the inner-most leaf-node of one of Beijing's most labrythnian hutongs next to a family that trained racing pigeons. My friend and I bonded over our study of Chinese language, classical guitar and our experiences in Beijing. I strongly considered his recommendation to check out 三体 (Three Body), the Chinese Sci-Fi novel about alien life in a solar system with three stars as he described it, but I never had the chance to read the book.

Almost 10 years later I came across across a preview for the Netflix production of "3 Body Problem" scheduled to come out in early 2024. With the possibility of loosing my job weighing heavily on me, I picked up the books on Amazon hoping to have something to if I was going to be layed off. Over the weekend I was able to read a few of the chapters on my Kindle. I had not completely forgotten how to speak Chinese, and I could easily look up words and translate entire paragraphs with Google Translate.

Chinese in numbers

Here's a quick primer on the Chinese language from a mathematical perspective. This will be helpful before jumping into using NLP and LLMs with Chinese text later in this article.

First, how many Chinese characters are there? This question isn't specific enough to have a single answer. A common rule of thumb that I have heard before says that there are over 50,000 characters in total with roughly 10,000 characters in use and about 3,000 characters frequently used in Chinese media and newspapers (source). This answer from StackOverflow's legendary #1 ranked user VonC gives a good answer based on the number of Unicode characters in the CJK Unified Ideographs block: 20,992.

Here are some numbers and statistics to be better understand the text of the Three-Body Problem Chinese text:

- 188,380 total charactes in the book

- 2,859 unique characters in the book

- 36 chapters in the book

- average of 69.78 paragraphs per chapter

- total of 2,512 paragraphs in the book

- average of 74.99 characters per paragraph

Character Frequency

Let's look at how frequently each character in the book is used. We can also combine this with some data on the overall frequency of Chinese characters. The best measurement I found for overall character frequency is from Middle Tennessee State University. Here's a visualization that shows of all of unique characters in the book. The height of a column represents how frequently a character occurs in the book, and the color represents the relatively frequency of the character in Chinese language overall.

Meta, LLMs, and Grass Mud Horse

In recent months I have been following the development of big open source AI projects. Two projects in particular are InvokeAI, an image generation tool based on Stable Diffusion, and LLaMA 2, the latest generation of Meta's open source LLM. The name LLaMA stands for 'Large Language Model Meta AI', which happens to be the same spelling as the word for the domesticated South American camelid: llama. Before going deeper into LLMs we need a quick Chinese lesson.

草泥马 is a non-technical word that referes to animals like Llama or Alpaca. It can be directly translated as "Grass Mud Horse" and it is phonetically similar to the most common Chinese profanity: 操你妈, which literally means "f*** your mother". The characters in these two words are nearly synonymous: the sounds of both words are "cao ni ma", but the tones are different, which in Chinese changes the meaning completely. The llama is basically a legendary Chinese internet meme subversive in the face of government censorship. 🦙 was approved as part of Unicode 11.0 in 2018. The extended version of this profanity is 草泥马戈壁 (Cǎonímǎ Gēbì: Grass Mud Horse Gobi), refering to the geographical origin of this mythical creature: the Gobi Dessert. This term is more explicit as it synonymous with "f*** your mother's c***". Coincidentally, the Gobi Desert is a region of Inner Mongolia which borders the mountainous region of Greater Khingan Range (大兴安岭), the location of Red Coast and Radar Peak in Three-Body Problem where Ye Wenjie makes first contact with the Trisolarians.

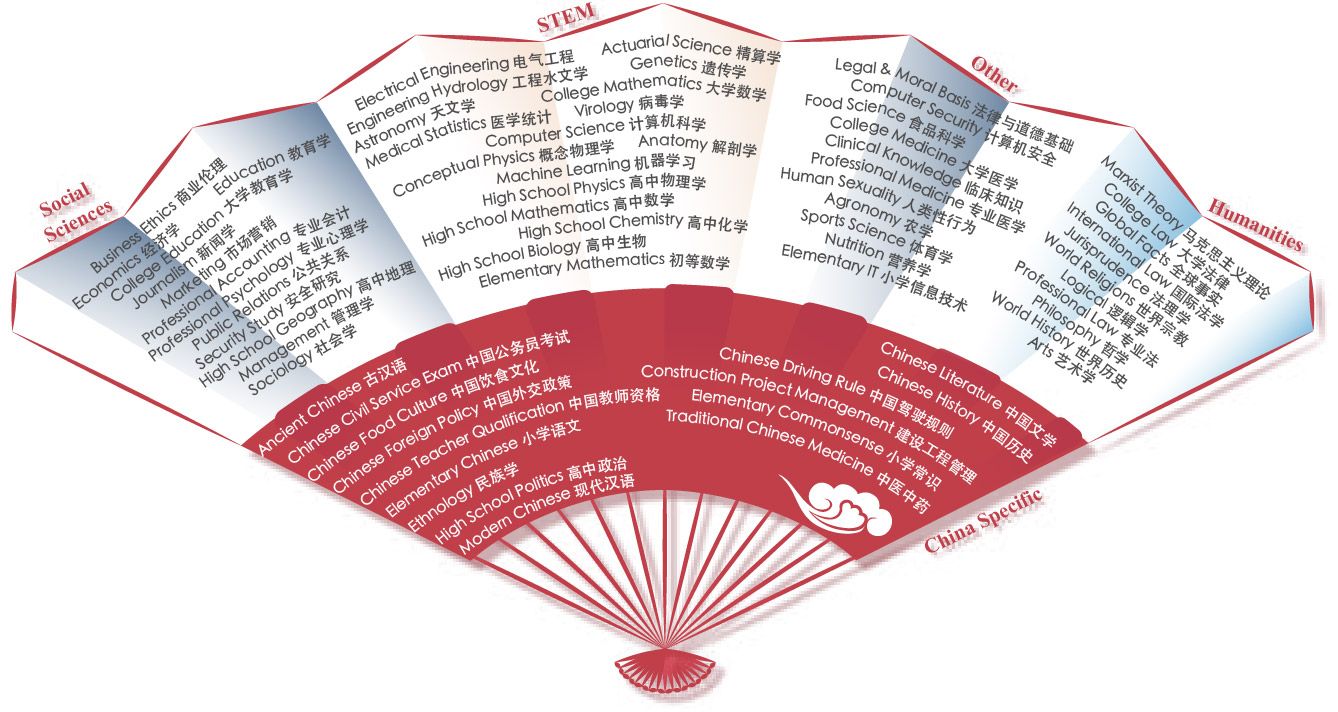

I requested access to Meta's LLaMa 2 models as soon as they came out and I was able to get it to run on my NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. I also joined a subreddit called r/LocalLLaMa with over seventy thousand members discussing how to run large language models on consumer hardware. Another annoucement that caught my attention in July was the release of Chinese LLaMa 2, an open-source large language model trained on Chinese and English which does very well against Chinese Language LLM Benchmarks such as the CMMCU: Chinese Massive Multitask Language Understanding.

Translation in and of The Three-Body Problem

There are two important plot developments related to language translation in the Three-Body Problem novel, both of which involve book’s main female protagonist Ye Wenjie. First, copying the translation of Rachel Carson's 'Silent Spring' leads to her being relegated to the Red Coast project. At the Red Coast Ye Wenjie communicates with extraterrestrial life through a universal translation technology developed by the top-secret project.

Ken Liu’s translation of the Three-Body Problem book from Chinese to English places the events during the Cultural Revolution at the beginning of the book rather than in the middle of the book. According to Liu, this was done in order to avoid attention of government censors, and his original intention was to tell the story in this way, starting with the events of the late 1960's in China.

I tried translating the Chinese text of the Three-Body Problem book using LLMs. I started with the Chinese-LLaMA-2 model and then tried Qwen-7B-Chat, Baichuan-13B-Chat when these models came out. I found that the Qwen-7B-Chat model worked best for my translation tasks. Qwen is short for Qian Wen (千问, or "one thousand questions") and is developed by Alibaba Cloud.

How do you get an LLM to translate text? Ultimately the quality of the translation returned by the LLM depends on the prompt and other parameters used for inference. I experimented with both chat and completion approaches and tried lots of different kinds of prompts. The models I worked with have a 4K context window (the number of tokens the model can take as input when generating responses), so for translation tasks I had the LLM work on one paragraph at a time. Here's the prompt I used with the Qwen-7B-Chat model:

"你是一名翻译。请将每条消息从中文翻译成英文。"

(You are a translator. Please translate each message from Chinese to English.)

I did some basic prompt engineering to get the LLM to translate the books in the Three-Body problem paragraph by paragraph. My computer was able to translate the first book overnight in under 500 minutes. Here are the results of my translation of Three-Body Problem with Qwen-7B-Chat model:

It was interesting to see the failure modes of translation tasks for the different models. Most of the time the LLM was able to provided accurate translations. Some of the failure modes I observed were:

- a few Chinese characters would show up in the English translations

- a complete Chinese sentence would show up in an otherwise complete translation of a paragraph

- The LLM refused to translate certain paragraphs that included violent imagery, such as the violent scenes from the Cultural Revolution chapters

- If the sentence it was asked to translate was a question, the LLM would respond in Chinese to the question rather than providing a translation of the question itself

Tokenization

When you feed a prompt to an LLM, it first puts the prompt through a process called tokenization. Tokenization takes a string of text and breaks it down into tokens (defined by the Large Language Model you are using). The process of tokenization is similar to the tokenization done by spaCy mentioned earlier. These tokens produced by LLM tokenization are numbers. Here's an example of tokenization in action using the Chinese-Llama-2 model:

import json

import os

from llama_cpp import Llama, LlamaTokenizer

llm = Llama(

model_path="/path/to/models/ggml-model-q4_0.bin",

n_ctx=4096,

n_gpu_layers=30

)

tokenizer = LlamaTokenizer(llama=llm)

TEXT="在那个已被忘却的日子里,它的世界颠覆了。泥土飞走,出现了一条又深又宽的峡谷,然后泥土又轰隆隆地飞回来,峡谷消失了,在原来峡谷的尽头出现了一座黑色的孤峰。其实,在这片广阔的疆域上,这种事常常发生,泥土飞走又飞回,峡谷出现又消失,然后是孤峰降临,好像是给每次灾变打上一个醒目的标记。褐蚁和几百个同族带着幸存的蚁后向太阳落下的方向走了一段路,建立了新的帝国。"

tokens = tokenizer.encode(TEXT)

print(str(tokens[:4]) + " ...")

1, 30505, 32380, 36812 ...

for token in tokens:

text = tokenizer.decode([token])

print(text, end=" ")

在 那个 已被 忘 却 的日子 里 , 它的 世界 颠覆 了 。 泥 土 飞 走 , 出现了 一条 又 深 又 宽 的 峡谷 , 然后 泥 土 又 轰 隆 隆 地 飞 回来 , 峡谷 消失 了 , 在 原来 峡谷 的 尽头 出现了 一座 黑色 的 孤 峰 。 其实 , 在这 片 广阔 的 疆 域 上 , 这种事 常常 发生 , 泥 土 飞 走 又 飞 回 , 峡谷 出现 又 消失 , 然后 是 孤 峰 降临 , 好像是 给 每次 灾 变 打 上 一个 醒目 的 标记 。 褐 蚁 和 几百 个 同 族 带着 幸 存 的 蚁 后 向 太阳 落 下的 方向 走了 一段 路 , 建立了 新的 帝国 。

english_text = "This is an example of tokenization using a large language model."

english_tokens = tokenizer.encode(english_text)

print(str(english_tokens[:4]) + " ...")

for token in english_tokens:

text = tokenizer.decode([token])

print(f"'{text}'", end=" ")

1, 4013, 338, 385 ...

'' 'This' ' is' ' an' ' example' ' of' ' token' 'ization' ' using' ' a' ' large' ' language' ' model' '.'

Here are some key differences between English and Chinese that have implications for how the language is tokenized by large language models:

- Chinese does not use spaces between words like English does

- Chinese words are typically formed from 2 or more characters

- Chinese verbs are not conjugated and do not have different tenses

- Chinese words don't have singular and plural variants

- Chinese grammar is very simple and is similar to English

- Chinese characters do not have capitization like ASCII characters

- The token represented by the number 1 encodes a starting token

Imagining scenes from Three-Body Problem with Stable Diffusion

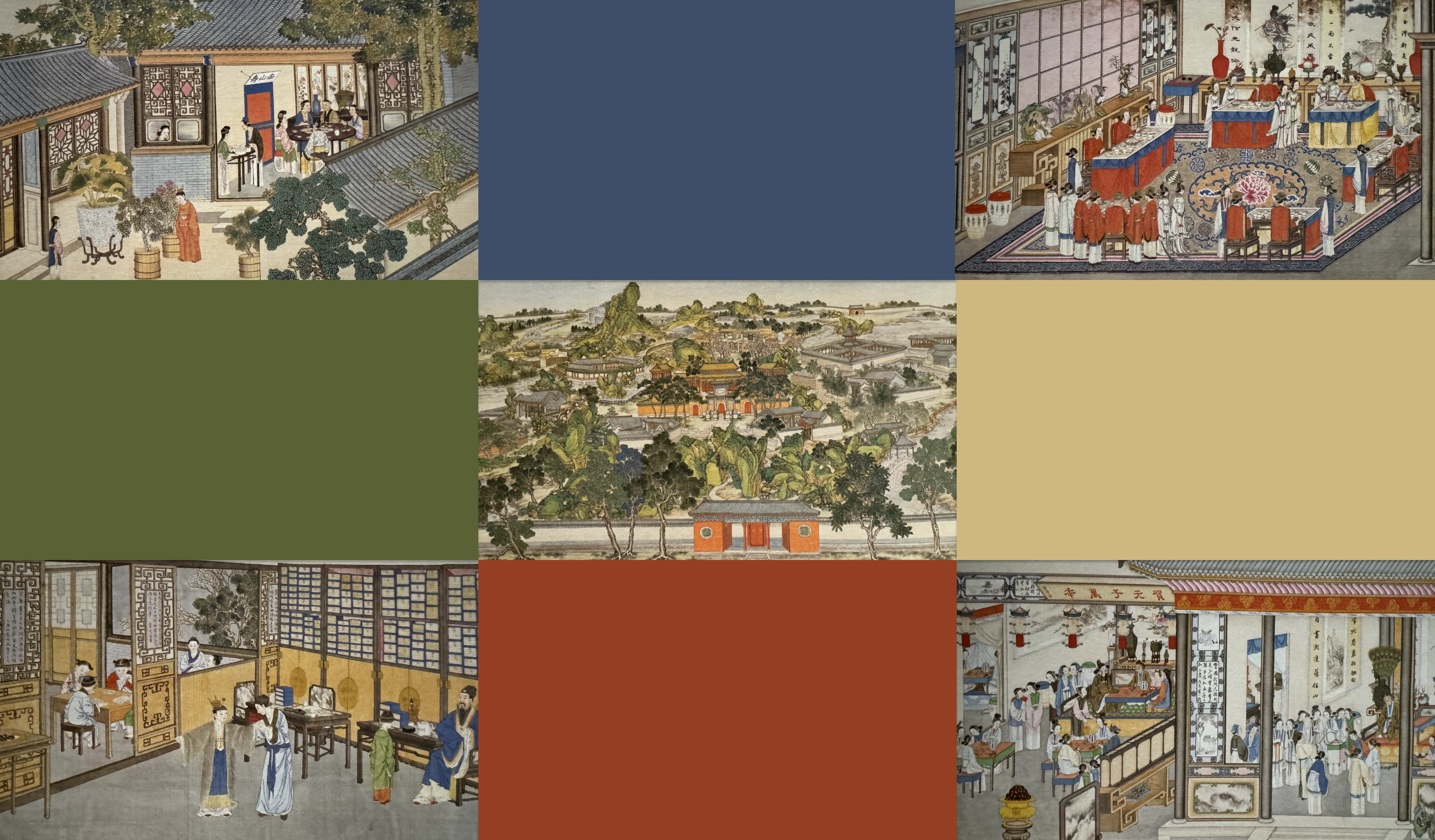

Here are some images I generated using Stable Diffusion with InvokeAI that depict scenes from the Three-Body Problem book. These scenes portray solutions to the Three-Body Problem that players in the Three-Body game devised. The first is a Confucian system of etiquette for predicting the movement of the three suns. The second is a human-powered computer that Qin Shi Huang used to try to predict the movement of the three suns.

Prompt: Ceremonies and etiquette system related to the sun and multiple celestial++ bodies Confucius artistic style

array of chinese++ warriors++ on a electronics+ circuit+ board qing+ dynasty style art logic puzzle

Congrats to the InvokeAI team on the 3.0 release. It has been awesome to use and the current docker compose setup is a huge improvement on the 2.x version.

n-body simulations, CUDA and Three.js

The nbody problem has no closed-form analytical solution, but it is possible to do a basic simulation of the three-body problem on consumer hardware and open source software, like NVIDIA and CUDA.

Three-Body CUDA simulation

I wrote a simple program with the help of ChatGPT for running nbody problem simulations. The program uses CuPy, a Python library that exposes APIs for doing matrix multiplication to predict the position of three bodies using Euclidian Integration. Here's the script:

import numpy as np

import cupy as cp

import time

import json

# Simulation parameters

NUM_PARTICLES = 3

DIMENSIONS = 3 # 3D space

NUM_STEPS = 30

DT = 0.1

# Generate initial positions and velocities

np_positions = np.random.randn(NUM_PARTICLES, DIMENSIONS)

np_velocities = np.random.randn(NUM_PARTICLES, DIMENSIONS)

cp_positions = cp.array(np_positions)

cp_velocities = cp.array(np_velocities)

np_ticks = np.expand_dims(np_positions, axis=0)

cp_ticks = cp.array(np_ticks)

# nbody simulation loop

start_time = time.time()

for step in range(NUM_STEPS):

# this gets pairwise differences

diff = cp_positions[:, None, :] - cp_positions[None, :, :]

distances = cp.sqrt(cp.sum(diff**2, axis=2))

# avoid division by zero

epsilon = 1e-5

inv_distances = 1.0 / cp.maximum(distances, epsilon)

# calculate forces

cp_forces = cp.sum((diff.T * inv_distances**3).T, axis=1)

# update velocities and positions

cp_velocities += DT * cp_forces

cp_positions += DT * cp_velocities

cp_ticks = cp.append(cp_ticks, cp.expand_dims(cp_positions, 0), 0)

sim_time = time.time() - start_time

print("Simulation time:", sim_time)

class NumpyArrayEncoder(json.JSONEncoder):

def default(self, obj):

if isinstance(obj, np.ndarray):

return obj.tolist()

return json.JSONEncoder.default(self, obj)

np_ticks = cp_ticks.get()

# this is data we can work with in python and write to a file

with open("ticks.json", "w") as f:

f.write(json.dumps(np_ticks, cls=NumpyArrayEncoder))

To better understand the matrix math here I walked through a simple example of what each step does:

# particle coordinates (x,y,z) in 3D space

positions = cp.array([[1,2.5,3], [4,5,6], [7,8,9]])

The first operation creates an array for pairwise distances for each dimension:

diff = positions[None, :, :] - positions[:, None, :]

print(diff)

array([[[ 0. , 0. , 0. ],

[ 3. , 2.5, 3. ],

[ 6. , 5.5, 6. ]],

[[-3. , -2.5, -3. ],

[ 0. , 0. , 0. ],

[ 3. , 3. , 3. ]],

[[-6. , -5.5, -6. ],

[-3. , -3. , -3. ],

[ 0. , 0. , 0. ]]])

The rows of zeros correspond to a particle's x, y and z distances to itself, which are all zero by axioms of Euclidian vector spaces.

The next operation calculates the distance between each particle:

distances = cp.sqrt(cp.sum(diff**2, axis=2))

print(distances)

array([[ 0. , 4.9244289 , 10.11187421],

[ 4.9244289 , 0. , 5.19615242],

[10.11187421, 5.19615242, 0. ]])

The diagonal or zeros represents that fact that a particle n has a distance of zero to iself.

The next step calculates inverse distances and uses a small epsilon value to avoid division by 0:

epsilon = 1e-5

inv_distances = 1.0 / cp.maximum(distances, epsilon)

print(inv_distances)

array([[1.00000000e+05, 2.03069233e-01, 9.88936353e-02],

[2.03069233e-01, 1.00000000e+05, 1.92450090e-01],

[9.88936353e-02, 1.92450090e-01, 1.00000000e+05]])

The next step is the most elegant part of the simulation and really flexes the GPU's parallel compute capabilities:

cp_forces = cp.sum((diff.T * inv_distances**3).T, axis=1)

The .T operation transposes a matrix, multiplies by the cube of inverse distances, then transposes the matrix again before summing along the first axis. Transposing a matrix basically swaps rows and columns.

The next two steps are also pretty elegant:

# update velocities and positions

cp_velocities += DT * cp_forces

cp_positions += DT * cp_velocities

In the last step I append the updated positions to an array that holds every "tick" (the positions of each particle between each time interval, DT - "delta time")

Here's the formula for the mathematical equation used to calculate the force on any given body in an n-body system:

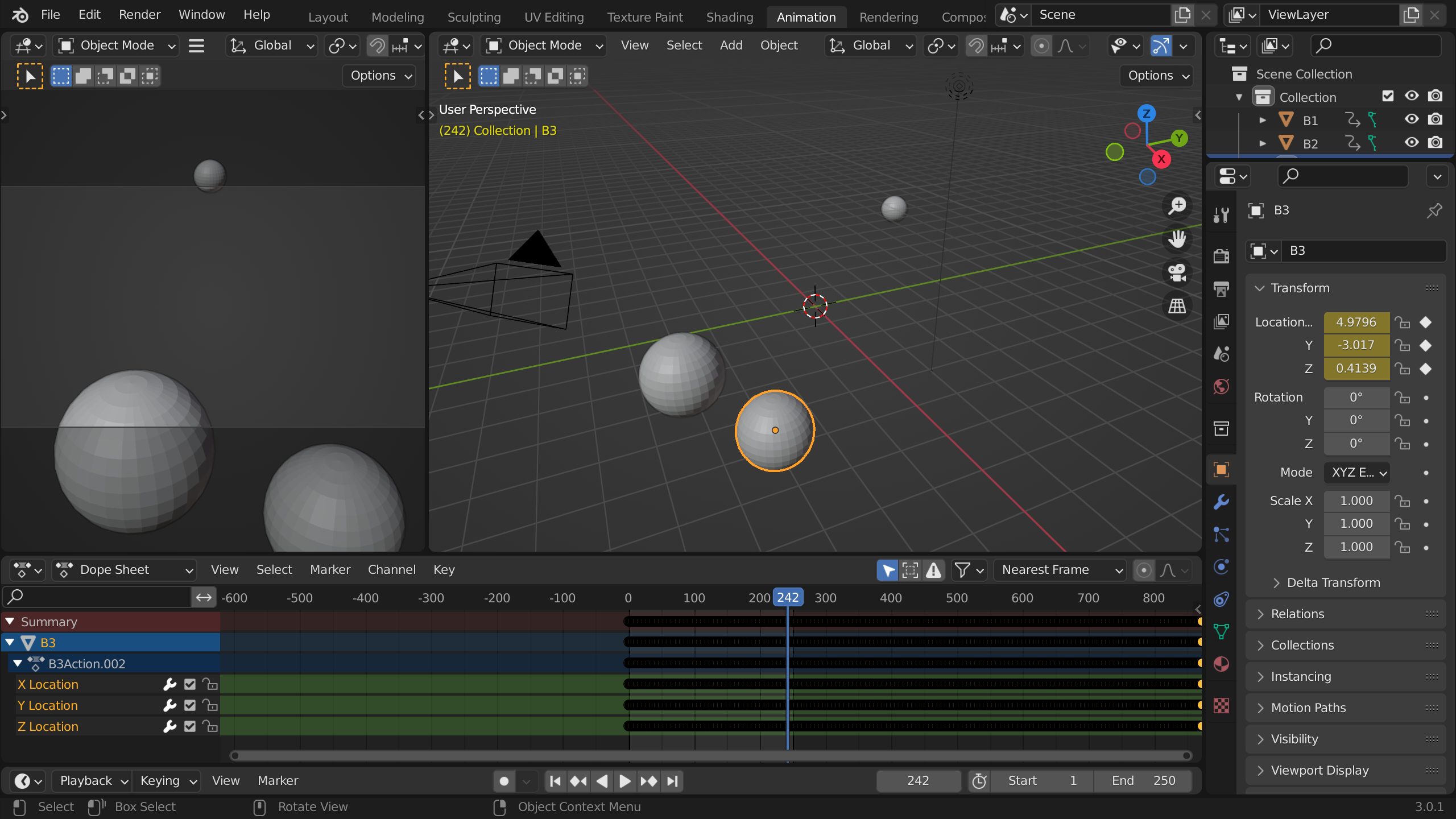

To test that the simulation was working correctly I used ChatGPT again to construct a 3D scene in Blender with a Python script:

Three.js

Imagine that we are working for a Chinese startup called the Qin Dynasty. The founder, Qin Shi Huang, is a brutal tyrant with an obsessive fear of assassination. Let's put on our product hat for a minute and think about how we can impress him with a clean solution to the three-body problem. A recent attempt involved building a 30,000-person analog computer that was destroyed in tri-solar syzygy. Failing to accurately predict the movement of the suns could mean execution by live-burial, a fiery death or worse. Using CUDA and Blender is a good MVP but doesn't make for the best technical demo since it involves so many different steps: running the simulation in CUDA, exporting data to JSON, loading data into a visualuzation and then finally rendering a video of the simulation. With a popular Javascript library called Three.js we can run an interactive three-body problem simulation in real-time right in the browser. Here's the three-body simulation I also co-authored with ChatGPT-4 using Three.js:

Screen adaptations, the gaming industry and the CCP

Dream of the Red Chamber is one of China's Four Great Classical Novels and is often seen as the pinacle of Chinese fiction. It was written in the mid 18th century and first published in 1791. It is a long saga that totals 960,000 characters in length, on similar scale to the length of the Three-Body Problem trilogy. Sun Wen, a Qing dynasty artist, spent 36 years of his life doing a series of 230 paintings depicting scenes from the Dream of the Red Chamber: dream sequences, demons, goddesses, nuns, nobles, beggars, raging fires, landscapes, interiors, wildlife, gardens, temples, funerals, battles, processions, banquets, trials, operas, marriages.

Following in this tradition of celebrating great literature, Tencent Video and China Central Television produced a 30-episode adaptation of the Three-Body Problem that was released in Feburary 2023. It is a surprisingly faithful reproduction of the book that is worth checking out. The portrayal of Shi Qiang (Da Shi) was easily my favorite part of the series. I was also impressed by how the Three-Body VR game scenes were done with computer graphics. It got me thinking about how China is represented in some of the worlds most popular video games.

This is Rocket League, a competitive vehicular soccer game where players, like in the Three-Body game, must master the laws of gravity. The Chinese-themed Forbiden Temple arena shown here is one of many virtual international venues in the game. Epic Games (creator of Fortnite) bought Rocket League in 2019 for an estimated $250 to $300 million.

Like Rocket League, Overwatch is a highly-competitive eSport on a global scale. It features a large roster of 38 players from all over the world. Dr. Mei-Ling Zhou (周美灵) is a Chinese climatologist who uses ice both to attack opponents and to defend herself. Mei became controversial in China due to her adoption as a symbolic figure in the 2019 Hong Kong protests.

Three college friends combined their interest in anime, comics and games (ACG) and literature to publish one of the most successful games created by a Chinese company and arguably one of China's most important cultural exports: Genshin Impact. miHoYo, the Shanghai-based company that develops Genshin Impact, grossed $4 billion of revenue globally in the game's first year setting a new record in the gaming industry. Like other companies of its size, miHoYo has a party committee under the Chinese Communist Party that influences the company's operations.

AI and layoffs in the tech industry

I have a positive attitude toward AI and its ability to supercharge the creative work we do, but I also think that replacing humans and AI-related layoffs should should be a part of the conversation. I wasn't impacted by the recent round of layoffs at my company, and I'm grateful to have the opportunity to work with a talented team on interesting problems in the health tech industry. I do have some solid references for folks in DevOps, product and backend and frontend engineering, and I’m happy to connect and share via LinkedIn.

Layoffs in both China and the U.S. have been pummled the tech sector over the last two years. New graduates in China are also facing a difficult job market. There are some popular expressions that paint a picture of the job market in China:

- 躺平 Lying flat: avoiding relentless work

- 九九六 996 Work culture: describes working from 9AM to 9PM, 6 days a week, a common work schedule for many Chinese employees

- 全职儿女 Full-time Children: Young Chinese are getting paid to be ‘full-time children’ as jobs become harder to find

- 35岁诅咒 The curse of 35: Ageism in China’s tech sector has workers fearing the “curse of 35”. Shout out to my fellow Year of the Dragon 35 year olds! 🐲

- 吃苦 Eat Bitterness: China’s Young People Can’t Find Jobs. Xi Jinping Says to ‘Eat Bitterness.’

It is an exciting time for AI. Elon Musk and Kaifu Lee have both recently released open-source large language models: Grok and Yi. Sam Altman was fired as CEO of OpenAI, then came back. Stable Diffusion just released a text to video model. AGI might already be here. In the U.S., we are going into our first presidential election cycle with AI fully turned on. Here's a link to The Three-Body Problem book on Amazon. Thanks for reading and Happy Thanksgiving!